I must confess that I feel compassion for monsters.

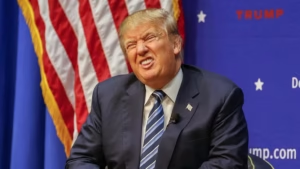

There is no disputing that Donald Trump is a monster.

A brute who should not be understood but restrained, like a rabid dog.

And yet — I feel compassion for him.

Not for the man, but for the child.

For the abused, pitiable five-year-old who resides within that ageing body.

How bewildered and terrified that child must be.

What must it be like to inhabit an adult body without adult responsibility, without the capacity to endure reality, without the ability to confront consequence?

Would not the end of that child’s suffering be something earnestly to be wished for?

With this thought in mind, I read the newly published United States National Security Strategy. A document which grants Europe two years to do what it ought to have done no later than 2014.

In this respect, the United States is correct.

Europe should have assumed responsibility for itself long ago.

At the very latest, during Trump’s first term, it should have become clear that the White House was occupied by a little boy whom Vladimir Putin was effortlessly manipulating.

But the true message of the strategy is not a call for European strengthening.

It is a declaration of a rupture in values. The United States no longer shares the principles upon which Europe has built its long — and often painful — alliance with it.

If one reads American history with even moderate depth, this development is hardly surprising. The United States is, at its core, a profoundly different and in many respects less democratic society than the European states. Its roots lie in Calvinism rather than the Enlightenment; in discipline rather than contract.

Trump is not an aberration, but a symptom.

His erratic policies have led some to believe that the United States is searching for a new role as a guarantor of democracy. The reality is the opposite: Trump and his Republicans admire dictatorship and despise freedom — precisely the freedom that Europe represents.

Read Machiavelli.

Neither princes nor monsters have friends. They have interests.

Alliances dissolve the moment shared interests disappear.

America’s role as the world’s policeman and defender of democracy has never been altruistic. It has been an exercise in self-interest. The difficulty, from the American perspective, has been that this role has simultaneously advanced freedom and democracy — often contrary to its own short-term interests.

In the new security strategy, this contradiction is resolved.

The document rebukes Europe for its democracy. Democracy and freedom are presented almost as repugnant, un-American phenomena. This is no rhetorical slip. It is a policy position.

The Trump administration regards Putin as a more natural ally than Europe.

Nor is this a temporary aberration. Trump articulated aloud what authoritarians usually merely imply:

“If you vote for me now, you will never have to vote again.”

This administration despises treaties, international institutions, and collectively agreed rules. These are seen as structures hostile to American interests. At the same time, the rest of the world — all who do not share this worldview — is defined as the enemy.

And in one respect, they are correct.

The rest of the world must indeed be the enemy of such a government.

Not out of hatred, but in order to survive

Vastaa